Here’s a short film from Beijing, China directed by Joewi Verhoeven. It’s an odd and discomforting tale about a solitary writer whose fictional world is intruding upon the real world. The film is a quiet and focused examination of a writer’s creative doubts and fears. I particularly like the bit where a Chinese policeman who is a friend of the writer comes over and can’t seem to see the dead body that is perhaps a result of the unrestricted imagination of the writer. The film also has a lovely soft celluloid look even though it was shot entirely on a Canon DSLR. Also, pay attention to the beautiful and eerie background audio.

Category Archives: Film

Filmmakers of Our Time: John Cassavetes – 1968 French Documentary

John Cassavetes’ first film was called ‘Shadows.’ It was made in 1959 and I think it might be the greatest film about race in America that’s ever been made. Cassavetes has always struck me as having an element of that required con-man aspect of the personality that is present in many good actors. When he talks he seems impressed with what he is saying and he knows how to deliver it with just the right amount of humor and a few self-deprecating remarks. But he means every goddamn word of it and he puts all of his thoughts into his film works. He’s one of those rare objects of confusion that sometimes crop up in American art. I’ve been watching a bunch of his films lately and I don’t think I’ve ever seen a filmmaker so interested in looking at the inability of the American adult to understand or even perceive the meaning of their habitual mannerisms. For me, his films illuminate what it means to be a grownup and how the performance required of grownups contrasts with what they really want to be.

Cassavetes on making ‘Shadows:’

That people can go out with nothing and through their own will and through their determination make something that exists… out of nothing. Out of no technical know-how, no equipment. There wasn’t one technician on the entire film. There wasn’t anybody who knew how to run a camera… walked in and started to read the directions of how to reload it. Got a Movieola and looked at it. Did all the things in the world and we made eight million mistakes. But it was exciting and fun.

This is a 1968 French documentary that was probably shot just after or during the making of his great marriage disaster film, ‘Faces.’

Trauma: A Video Poem Triptych by Swoon

Swoon is a Belgian poet filmmaker who makes films that try to blur the boundary between written poem and moving image. He mixes his own footage with found footage and sometimes mixes his own words with others. I like the quiet easy tone of his work. I like his manipulation of imagery. His work is a very difficult kind of work because it tries to make something new from two different things. Poetry is a perfect form all by itself. But film is never satisfied. It’s always looking for something to include within it. So it’s natural for film to go looking for poetry and try to bring it in. But poetry resists all alliances. Poetry seems content and willing to wait for centuries. It requires nothing. It doesn’t care what film wants. It will sit on a dry page in some crowded shelf somewhere waiting six hundred years for just a single pair of eyes to come along in boredom, open to the page, glance in, read half-way down and then slap the book shut for another six hundred years until someone decides to finish reading the goddamn thing. That’s patience. Film doesn’t have that. Film must be seen now or it withers. It begins to rot. Even if it’s digital. Digital films become confused and get lost in the forest of other digits. They may never find their way out again. So working with the two things and trying to get them together is very difficult but may actually make perfect sense.

This is a film poem triptych that is Swoon’s first work to include his own words. There’s a site for the film with more information.

Celles Qui S’En Font: 1928 Short Film by Germaine Dulac

Germaine Dulac was one of the original French film ‘auteurs.’ She was also a film theorist and feminist. She had a relatively short career as an avant-garde filmmaker, making such works as ‘The Smiling Madam Beaudet (1923) and ‘The Seashell and the Clergyman’ (1928) which is often credited as being the first Surrealist film.

In this film, the title translated as ‘Those Who Make Themselves,’ we follow a destitute drunk woman who appears to yearn for the life of a prostitute or to engage in some sort of tryst. It is also possible that she is simply despondent over rejection by a lover. She appears to fail at everything she tries and eventually walks down a staircase into the Seine river. It’s a very simple film that manages to convey a deep sense of loneliness.

Dulac insisted on being credited as the author of her films, not accepting the standard partnership between a screenwriter and director.

Here’s a 1923 quote from Dulac:

I believe that cinematographic work must come out of a shock of sensibility, of a vision of one being who can only express himself in the cinema. The director must be a screenwriter or the screenwriter a director. Like all other arts, cinema comes from a sensible emotion … To be worth something and “bring” something, this emotion must come from one source only. The screenwriter that “feels” his idea must be able to stage it. From this, the technique follows.

Here’s a Senses of Cinema article on Germaine Dulac entitled ‘The Importance of Being a Film Author: Germaine Dulac and Female Authorship.’

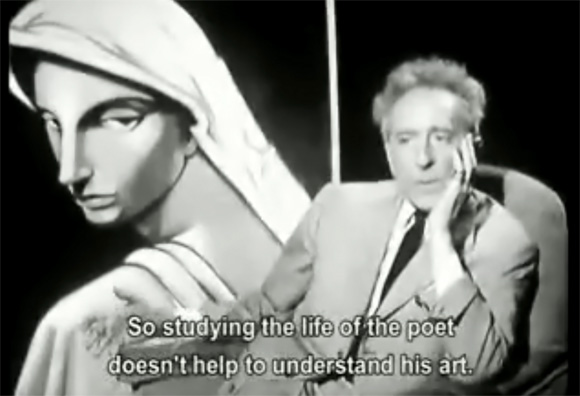

Jean Cocteau – Lies and Truths: 1996 French Documentary

This is a 1996 documentary by Noël Simsolo, featuring many interviews with Jean Cocteau himself, Jean-Luc Godard and actor Jean Marais. The great French director of films like ‘Blood of a Poet,’ ‘Orpheus,’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ was also an essayist, poet, artist, and playwright. When I was a kid I read the book he wrote about filming ‘Beauty and the Beast.’ I understood little of it except that there was the general impression of someone working against constant hardship to attain a mysterious something. The book detailed his struggles with the subtleties of light, weather and performance in the pursuit of a mysterious quality that must be present in the fairytale. I knew that his efforts had worked because I had seen the film on television and understood that it was simply the most convincing fairytale I had ever seen. Another film with this totally mysterious quality is ‘Orpheus,’ which is Cocteau’s modern version of the Greek myth in which the great musician/poet descends into the underworld to bring his wife back to the world of the living. Cocteau’s telling of the tale is at once ancient and modern, always mysterious and always trying to get close to poetry. Whenever I see that film I feel that I am seeing an important picture of French artistic life in the late 1940s told through the prism of ancient Greek myth. The film sits in that fascinating period of artistic ferment and dawning of a new cinematic movement that was a reaction to the end of World War II. Possibilities in films of that period seem limitless. There is a calmness of the image, an almost casual approach to creating scenes. Things are becoming more fluid and less studio-bound. Films are beginning to lean toward poetry and art.

Even though I never really understood what was being said in the ‘Orpheus’ film, it is probably one of the most important influences on the little bits of work that I do in film and video. Various images and scenes from ‘Orpheus’ regularly pop into my head as I work.

One of the best things I think an artist can learn from looking at Jean Cocteau is to follow one’s own interests without worrying about being unqualified – pretending can eventually get you where you want to go if you do it absolutely.

A Colour Box: 1935 Abstract Direct Paint on Film Animation by Len Lye